One of the country's biggest banks is calling for "big, bold, urgent" action to stop house prices rocketing even further, saying a "managed supply-induced decline in house prices" would be better than the possible alternative - a "painful correction".

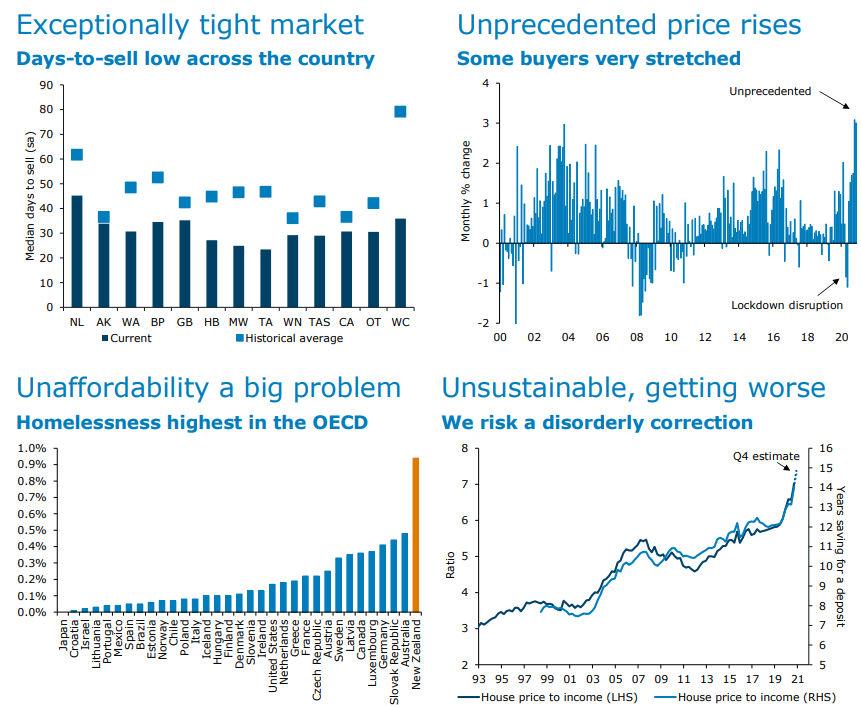

House prices in New Zealand have lifted about 20 percent in the past year, despite the recession - the combination of a lack of supply and low interest rates. Median prices are now above $700,000 nationwide and $1 million in Auckland, where a third of the country lives.

One political party leader has warned of a "wicked divide" between the haves and have-nots if it continues, and a prominent economist says the growing gap is "ripping apart the social fabric of New Zealand", with fewer Kiwis in their own homes than at any other time in the past 70 years.

"A co-ordinated Government policy response is urgently needed to stem continued price rises, acute housing unaffordability, and the large house price swings to which our market is vulnerable," ANZ Bank warns in its latest Property Focus report, out this week.

The median house price - $749,000 - is now more than seven times the median household income - $102,613. In the 1990s it was barely above three times. Then, it took about seven or eight years to save for a deposit - now, saving at the same rate, it takes 15.

"Not surprisingly, home ownership has fallen for all age groups, but especially for younger people," the report reads. "And it's not just home ownership that is out of reach. Rents are expensive too and have risen faster than incomes in recent years."

The "unprecedented" cost of housing is "an enormous part of the problem of endemic homelessness and deprivation" in New Zealand, the report says. Data shows our homeless rate is by far the worst in the OECD - more than double than it is in Australia, the runner-up - and there is significant overcrowding.

"The heart of the issue of housing unaffordability is that not enough homes have been built to meet the growth in our population, and housing supply has not been sufficiently responsive to changes in demand, financial conditions - and price."

New Zealanders have favoured pouring money into property instead of productive investments since the 1987 market crash. Investors say it's been a foolproof way to make money - Ashley Church, former head of the Property Institute of New Zealand, telling The AM Show in November values double every seven to 10 years, regardless of what moves the Government and Reserve Bank make.

He said it's time people accept it's inevitable prices will continue to go up, and focus on finding ways to get people onto the ladder. But ANZ says it's unsustainable and "just doesn't add up" when compared with much slower income growth.

"The longer the party goes on, the more financial vulnerabilities increase, and the greater the risk of a correction."

Both Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and Grant Robertson, mindful that many Kiwis are banking on capital gains to fund their retirements, have said they don't want to see house prices come down- even as fewer and fewer Kiwis are able to afford them.

ANZ says both they and the public need to change their attitudes.

"Policymakers and the public both need to be willing to accept house price stabilisation or even gradual real house price declines. Not only would this help affordability; a managed supply-induced decline in house prices is a much better outcome than a painful correction, which is a risk under the current market structure."

Rather than being impossible, as Church would suggest, ANZ says post-quake Christchurch shows it can be done. Since 2015, prices in Selwyn have gone up only 2 percent - a fraction of the nationwide increase of 37 percent.

"Given income gains, house prices in Selwyn have been getting gradually more affordable. This is despite very strong population growth, with the population increasing 60 percent since 2011."

Selywn's done it through releasing more land, having minimum density requirements, streamlining consents and having a long-term plan, ANZ says.

Data from Statistics NZ and QV, graphed in the report, show the more housing an area adds per capita, the slower prices grow.

Put simply, ANZ recommends three big moves.

1. Freeing up buildable land

"Because buildable land is so scarce and expected to remain so, this has been capitalised into very high land prices. An enormous portion of the cost of a house is the cost of the land it is on - up to 56 percent in Auckland."

Even if it takes time to build infrastructure, signalling in advance more land will soon be available could stop expectations of scarcity being "baked in" to house prices, ANZ says. And there is room inside existing boundaries that could be used to build more housing, because "a small, homogenous house is much better than none".

"As a wise person once noted, property owners tend to be raging libertarians as regards their own property rights, and complete socialists when it comes to their neighbours' - without even recognising the contradiction. To achieve real change, existing home owners need to be willing - or forced - to embrace some combination of urban expansion and intensification."

2. Building more houses and infrastructure

"A central Government-organised build using cheap, mass-produced options to make it happen could be part of the answer."

ANZ welcomed the Government's recent moves to increase the number of tradies, but says there are still bottlenecks in the supply of materials and prescriptive rules and regulations that have resulted in " a near-monopoly to certain products for which perfectly good alternatives are available".

3. Aligning demand and supply

"Curbing immigration cycles would reduce pressure on the housing stock. It’s still important to meet skill shortages, but with the border currently closed, it's a good opportunity to take a good hard look at migration settings and what is really best for New Zealand now and into the future."

ANZ also says while initiatives to get first-home buyers into the market through subsidies are "well-meaning", in the long-run they just push prices up further.

"Incentives to reduce the attractiveness of property investment would perhaps be desirable to impact the composition of the market, even if not a game changer for affordability. The most effective way to reduce the attractiveness of property investment is to reduce the scope for capital gains by increasing supply."

A capital gains tax, on the other hand, is "worth considering for broader reasons, like intergenerational equality", but would only have a very slight effect on house prices, "similar to the ban on foreign buyers".

Conclusion

"Fundamentally, focus needs to be on those changes that will make the biggest difference and lead to significant, sustained impacts," the report concludes.

"First and foremost, that means tackling the issue of supply constraints. Sure, it's complicated and some aspects of the response may take time, but doing nothing simply isn't an option. The need for action is urgent. There's potential for meaningful change, but we must act now."