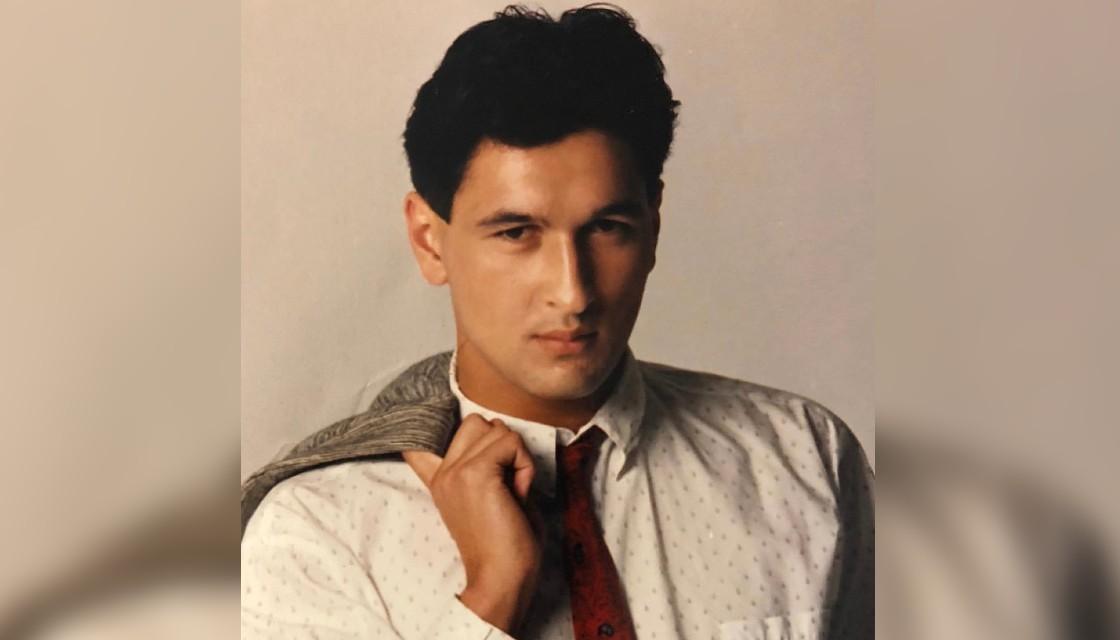

It was a Christchurch winter's morning in 1987 when I first realised being a journalist who has whakapapa Māori comes with certain responsibilities and expectations, whether you want them or not.

I was 21 and working for RNZ. My editor had sent me to report on the ground-breaking Te Māori exhibition that was travelling the country. It was a big event for the city and I wondered why they'd given such a plumb assignment to such an inexperienced reporter. I quickly realised it was because I was Māori and none of the other, non-Māori reporters felt comfortable covering it.

I loved it and felt an immediate connection. My editor later congratulated me for bringing such "fresh eyes" to my coverage. Āna, they were fresh alright; I'd never seen anything like it.

My father is Ngāti Kahungunu from Wairoa and he met my Pākehā mother in Ōtautahi while on a Māori Affairs Trade Training scheme. While we had frequent trips back to Wairoa I was very much the product of a "Pākehā-fied" Canterbury and its schooling system. There was nothing really in place to learn te reo Māori or indeed any aspects of Māoritanga back then. I have a vague recollection of making poi and learning Pōkarekare Ana at primary school and that was about it. Koinā noa iho.

For many years I looked with some envy at the opportunities my younger siblings were given and wished I'd had the same. My sister Kelly flourished in learning Te Reo.

Throughout my early career, there were instances where my lack of Te Reo caused me great anxiety. I dealt with it by putting it into the "too hard basket" - the whakamā I felt I justified by describing myself as a journalist who is Māori, and not a Māori journalist.

It was a double blow as while I had the cultural traits that often deter young Māori or Pasifika people from pursuing journalism, i.e. reluctance to challenge authority or elders and not feeling like I had a valid or relevant voice, I had none of the Māoritanga knowledge or tools. Tino koretake nei, I felt ripped off.

Some years later while working in current affairs I realised that while aspects of being Māori aren't conducive to being a good journalist, many are. We're often great storytellers and have a natural empathy - or Manaakitanga - and humour. And of course, we bring a different perspective - he tirohanga Māori tērā (a Māori viewpoint).

The reluctance I'd felt to stand up for or push myself in my early career I flipped on its head and became a champion for others. It helped enormously, particularly since many of the underdogs I went into bat for were Māori.

Once after running a series of stories to prevent a health clinic in Te Tai Tokerau - the far north - from being closed, members of the iwi travelled down to Auckland to present me with a specially carved Patu. It is a much treasured Taonga.

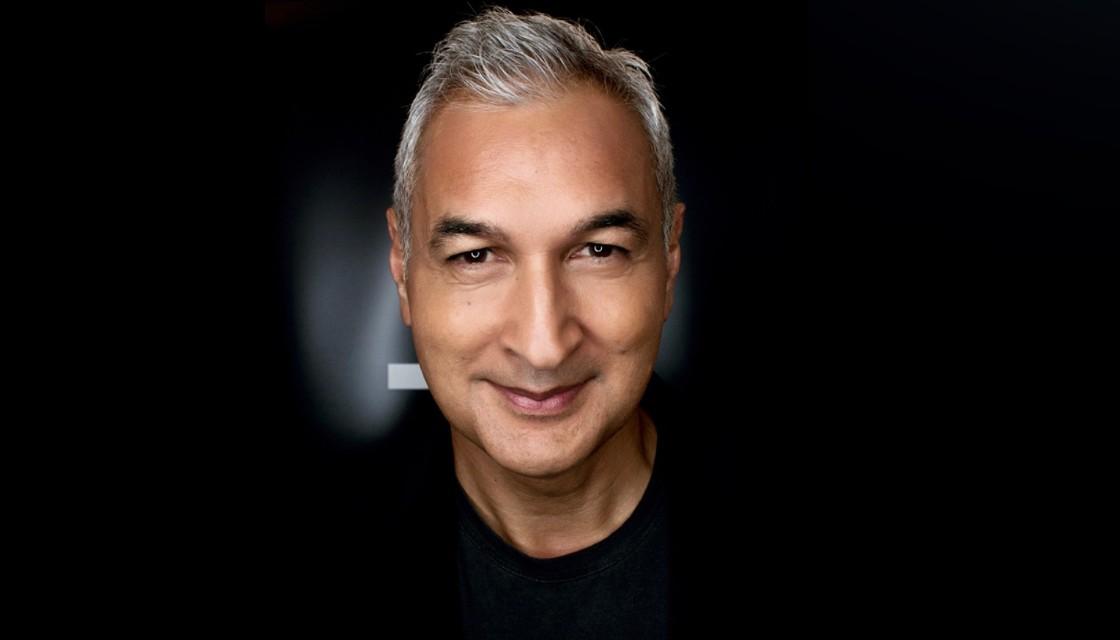

Being Māori and in a prominent role in mainstream media is now a responsibility I embrace. I remember one of my first times presenting the news on Three, I was anchoring alongside Carol Hirschfeld (Ngāti Porou) and sports presenter Clint Brown (Fijian). I felt a keen sense of pride in the fact that three brown faces were hosting a national network's flagship news show. The moment wasn't lost on my brother Kerry in Christchurch either who mischievously texted to say "what the hell is this - Te Karere?"

But it's about more than optics or the colour of your skin. It's what you feel inside rather than how you look outside that matters most. I've gained the greatest confidence in being a Māori journalist by embarking on a Te Reo journey. And it is a journey with many stops and starts along the way.

And for that reason, I feel like Te Wiki o Te Reo Māori has run parallel to my own pursuit of Tikanga Māori, decades in the making and slowly but surely gaining confidence. Kia kaha, kia māia, kia manawanui (Be strong, be brave, be steadfast).

This article was made in support of Toru and Te Wiki o te Reo Māori in partnership with Te Māngai Pāho.