With Wednesday's announcement the minimum wage would go up another $1.20 next year, the usual arguments for and against it were trotted out.

"With our economy doing well, we want to make sure that our lowest-paid workers also benefit," said Workplace Relations and Safety Minister Iain Lees-Galloway, talking up the move to $18.90 from April 1.

While E tu union spokesperson Annie Newman called it a "really good start" that would make a "big difference" to those struggling on the breadline.

"We've got a member here who's a security guard and she works about 70 hours a week to feed her family. When she gets that increase, she can look to cutting back on a few hours."

But David Seymour, leader of the right-wing ACT Party, said people would lose their jobs as a result.

"People miss out on jobs, the costs for businesses go up, consumers shift away from the businesses that are supposed to be employing the people we're trying to help," he told Magic Talk on Friday.

That's also the view many business leader hold.

"It's a fact people will lose jobs," Max Whitehead of human resourcing consultancy Whitehead Group. "Some businesses can't cope and it will cost jobs."

But what's the reality? Newshub's dug up and crunched the numbers.

How the minimum wage has changed over time

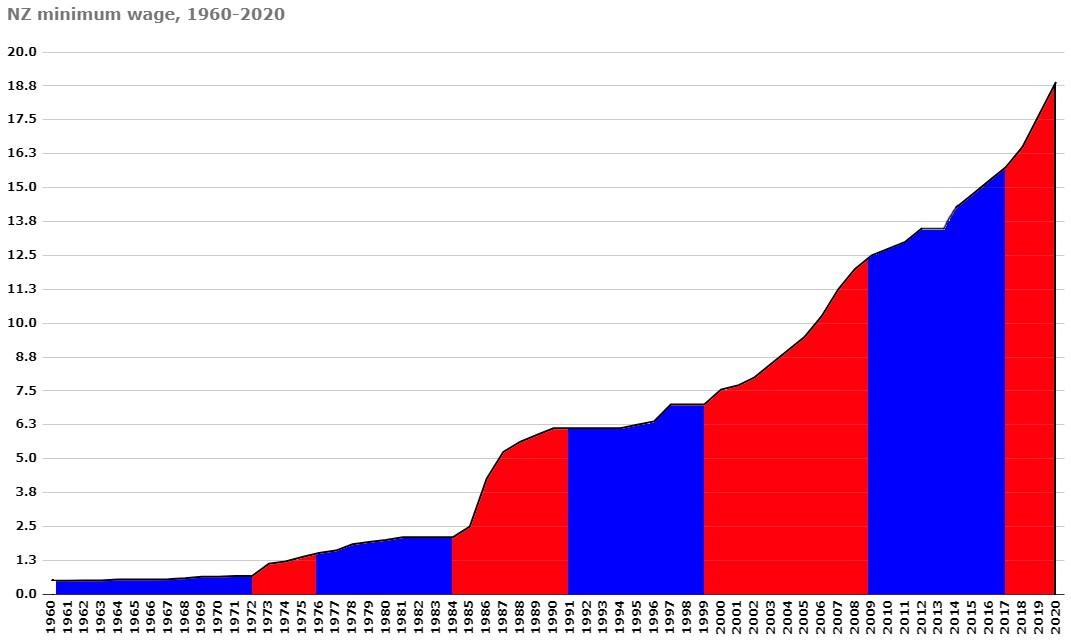

Documents show New Zealand's minimum wage in 1960 was just under 50c (converted to decimal). It's risen most years since then, with a few exceptions - usually under National-led Governments.

Its lowest, when compared with the average wage, was 30.1 percent and came in 1984, at the end of Robert Muldoon's term, according to a 1994 analysis by the Business Roundtable (now known as the New Zealand Initiative).

By 1986 the minimum wage had more than doubled - most of that coming between 1985 and 1986, when the David Lange-led Labour Government upped it 70 percent.

Between 1960 and 1972, the National Government increased the minimum wage about 3 percent a year. That was followed by:

- 34 percent a year by Labour under Norman Kirk and Bill Rowling

- 6 percent a year under Muldoon

- 32 percent a year under the Fourth Labour Government in the 1980s

- 1.5 percent under National in the 1990s

- 8 percent under Helen Clark's Labour

- 3.4 percent under National's John Key

- and 6.6 percent so far under Jacinda Ardern.

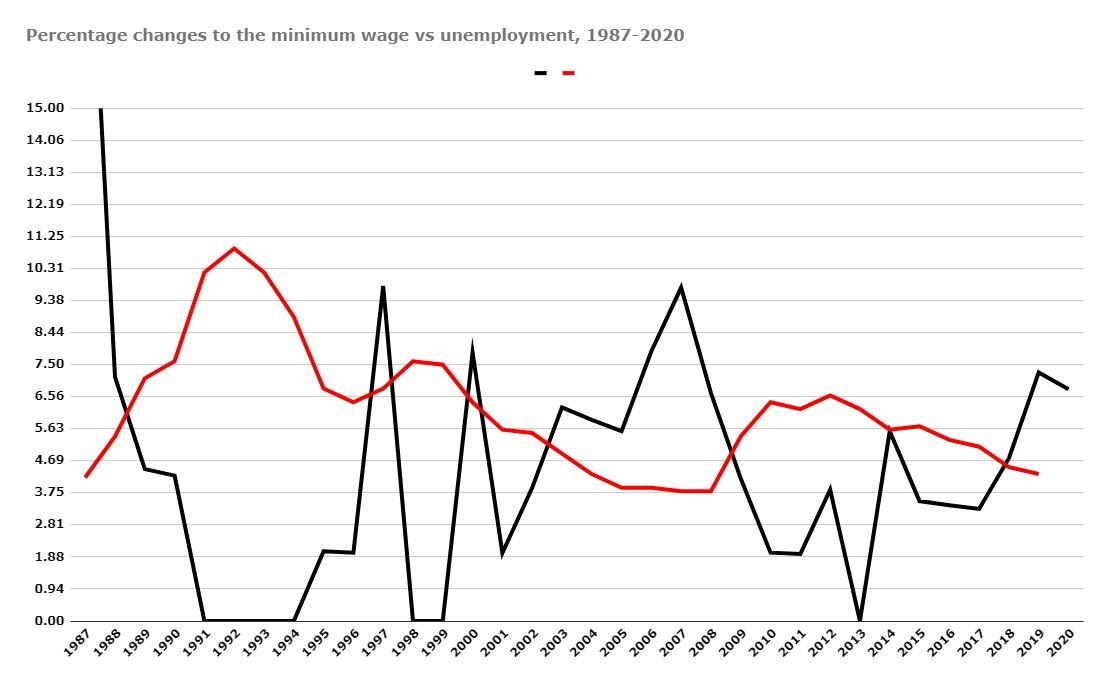

What effect on unemployment has it had?

Unemployment through the 1970s was low, by modern standards - staying under 2 percent, according to Reserve Bank documents. The big increases in the minimum wage enacted by Labour in the early 1970s appear to have had no impact, with unemployment even falling a bit after Muldoon took over and kept the rises coming.

Unemployment rose sharply in the early 1980s, pipping over 5 percent in 1983, after three years without any increase to the minimum wage.

The late 1980s and early 1990s saw unemployment spike up, despite markedly different approaches from Labour (1980s) and National (1990s). After the aforementioned huge increase in 1986, Labour kept the minimum wage rising even as unemployment rose to around 7 percent.

National took over in 1990 and didn't raise the minimum wage for four years - during which time unemployment reached 11 percent. It hovered around 7 percent in the second half of the decade, during which National increased the minimum wage only a small amount - from $6.25 an hour in 1995 to $7 in 1999.

Labour's nine years under Helen Clark saw regular single-digit increases to the minimum wage, as unemployment fell to levels not seen since the 1970s.

Unemployment began to increase at the end of her third term as the effects of the global financial crisis began to felt. National's next nine years in charge saw regular increases to the minimum wage, albeit smaller than Clark's.

Unemployment began to fall again from 2012, and has continued to do so under Ardern, despite minimum wage increases rising back to levels comparable to under Clark.