The largest ancient human skull ever found belongs to a new species previously unknown to science, according to three blockbuster papers published on Saturday (NZ time).

Homo longi, which translates to 'Dragon Man', is even more closely related to us than the Neanderthals according to Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London.

He is one of the scientists behind a new study into a skull known as the 'Harbin cranium', which has been kept at the Geoscience Museum in Hebei GEO University.

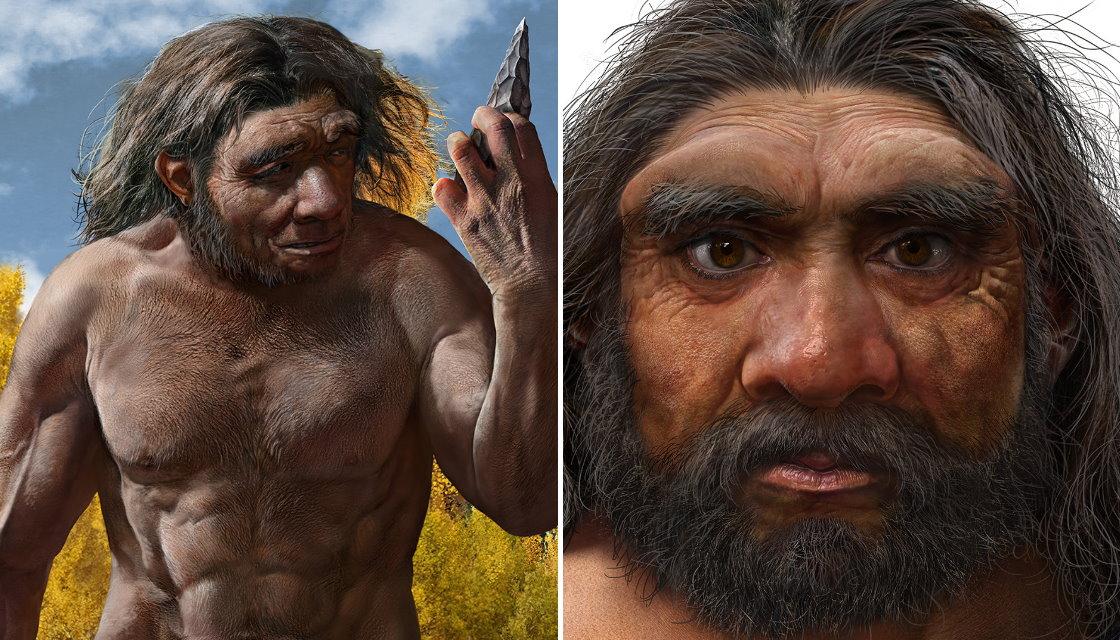

Found in the northeastern Chinese city of Harbin in the 1930s, the skull is about the same size as a modern human's but has a wider mouth, "huge" teeth, thick brow ridges and - most curiously - massive, almost square-shaped eye sockets.

"The Harbin fossil is one of the most complete human cranial fossils in the world," said co-author Qiang Ji, a professor of paleontology of Hebei GEO University.

"This fossil preserved many morphological details that are critical for understanding the evolution of the Homo genus and the origin of Homo sapiens."

Homo sapiens is us, modern humans. Other species of human died out tens of thousands of years ago, including the Neanderthals - although interbreeding means many of us still carry a bit of their DNA.

But analysis of the Harbin cranium suggests they're not our closest relatives on the tree of life - it's Homo longi, which evolved in eastern Asia parallel to Homo sapiens, which was just making its way out of Africa at the time.

The skull appears to have belonged to a 50-year-old man who lived at least 146,000 years ago in a small community in a forested floodplain environment.

"Like Homo sapiens, they hunted mammals and birds, and gathered fruits and vegetables, and perhaps even caught fish," said co-author Xijun Ni, Hebei GEO University professor of primatology and paleoanthropology.

Homo longi likely met and perhaps even co-existed, the scientists say, based on known migration patterns .

"If Homo sapiens indeed got to east Asia that early, they could have a chance to interact with H. longi, and since we don't know when the Harbin group disappeared, there could have been later encounters as well," said Dr Stringer.

And despite no longer being with us, Homo longi was no slouch.

"This human was massive in size," says the study, published in the journal The Innovation.

"This human lineage must have been as successful as the early H. sapiens populations in Africa and the Mideast, because they distributed in a very large area, including some extreme environments (high altitude and high latitude)."

Further analysis suggests Homo longi and Homo sapiens split on the evolutionary tree well after the Neanderthals, making them our closest known relative.

"The divergence time between H. sapiens and the Neanderthals may be even deeper in evolutionary history than generally believed, over one million years," said Dr Ni, who in 2013 announced the discovery of the oldest primate fossil ever found - 55 million years.

"Altogether, the Harbin cranium provides more evidence for us to understand Homo diversity and evolutionary relationships among these diverse Homo species and populations. We found our long-lost sister lineage."